Surface water and groundwater are essentially the same resource, but they are found in different locations across the Earth. Surface water is located on the surface of the Earth, such as rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and the ocean. Groundwater is found beneath the Earth’s surface in the space between rocks or sediments.

Both surface water and groundwater are part of the hydrologic cycle, the cycle water makes as it moves from ocean to atmosphere and back. Changes in either water source will affect the other, so using either resource requires significant care and management.

Surface Water

Thirty-seven percent of California’s annual rainfall becomes surface water. Out of the average 182 million-acre feet (MAF) we receive each year, 17 MAF is diverted into 41 reservoirs and 1200+ miles of canals.

Most of California’s rain arrives in the north and must be moved to serve communities in the south. Federal, state, and local governments have all built systems to move water including the Central Valley Project, State Water Project, and the Colorado River.

Groundwater

Groundwater is found in aquifers – rock or sediment that store water – and is a key supplier of California’s water needs. Most of our groundwater is used for agriculture (79%), and the rest is split between urban (19%), environmental (2%), and recreation.

Several factors affect groundwater development:

- Physical – porosity, hydraulic conductivity, and transmissivity of aquifers

- Quality – contamination (chemical or seawater)

- Economic – depth or cost of treatment

- Environmental – need to maintain for wetlands, streamflow, habitat

- Institutional – management plans, adjudication, ordinances

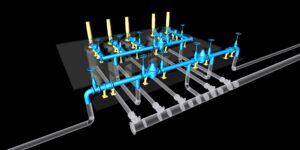

Groundwater actually moves based on potential energy, from points of recharge to points of discharge/extraction and back. Inflow comes from precipitation, seepage from canals, general recharge, and subsurface movement. Outflow is due to wells, discharge to the surface, and subsurface movement.

Extraction

California extracts most of its groundwater through wells for agricultural and domestic purposes. Groundwater extraction is regulated by both state and local agencies.

Hydrographs visualize groundwater changes and help public agencies determine if our aquifers can be extracted from or if they need replenishment. Too much groundwater extraction and not enough replenishment results in an overdraft of groundwater. These overdrafts can result in subsidence, or a sinking of the earth, as groundwater is responsible supporting the basins they dwell underneath. Currently, subsidence has impacted over 2,900 square miles of California.

Recharging

Groundwater recharge occurs naturally and through conjunctive use programs (coordinated usage of surface water and groundwater). “Water Banking,” allows groundwater to be recharged in a wet year and extracted or exchanged during dry years.

Quality

Groundwater is typically low in organics, but human activity can lead to serious contamination. The most common contaminants in California’s potable water wells are arsenic, nitrate, 1,2,3-TCP, uranium, and TDS.

Shallow groundwater sees higher levels of nitrate and manmade chemicals, while deep groundwater is more contaminated by arsenic and alpha activity. California produces a groundwater update every 5 years which summarizes the occurrence and nature of groundwater, defines boundaries and water characteristics of basins, and provides information on groundwater management. Read the 2020 Draft here.